The weeks before the 2014 independence referendum felt revolutionary. Activists pounded the pavement in villages, towns and cities across Scotland, fighting miniature skirmishes in a wider war between Scottish popular sovereignty and British state subordination. Radical demands like nuclear disarmament, breaking from Conservative austerity and the ending of child poverty were commonplace. Meanwhile, the British media and politicians mobilised in panic as support for change grew.

It’s frustrating to see fellow socialists and left-wing radicals fumble the issue of Scottish independence. It’s painful to see ordinary people losing their faith in it. But why should we lie to ourselves? The radical democratic vision for Scottish independence now faces the greatest challenge it has faced since the loss of the first referendum in 1979.

James Foley and Ben Wray, with the help of the late Neil Davidson, neatly address the present predicament in “Scotland After Britain”, a book published 8 years in the wake of the momentous Scottish independence referendum (indyref).

Today, the vibrant grassroots energy of 2014 is gone. The independence movement once threatened the British ruling class, prompting a disinformation campaign larger than the one that defeated Jeremy Corbyn, but now it has shrivelled to a few divided camps, overpowered by the SNP’s voice of reason and business sensibility. The hundreds of campaign groups that once called for self-rule and “bairns not bombs” have dwindled in a movement-decline carefully managed by the Scottish National Party. The defiance of Thatcherism and Western imperialism which ran deep in the veins of the movement in 2014 has given way to compliance with the orders of the European Union, NATO and neoliberal policies.

This deterioration of the independence movement has been felt by the entire left, but few have articulated this as comprehensively as this book.

Scotland After Britain dedicates many pages to thoughtful analysis of Scottish politics today. In a succinct manner, its authors outline the political-economic developments which created the SNP, its internal factions and how the miscalculations of New Labour allowed it to dominate Scottish politics.

Chapters 2 through 5 are its strongest sections. They summarise the context of the socialist movement in 21st century Scotland and develop a continuity of working-class resistance between Thatcher, the 90s consensus, New Labour and Tory Britain. Through these pages, readers are reminded of the transformative potentials of independence that won over people from the most deprived areas of the country ten years ago, dismissing Labourist assessments of working-class voters as being “obsessed with flags”.

Foley and Wray’s account of recent Scottish political history ends with an SNP still refusing to confront Westminster with a combative strategy. Despite repeated overwhelming victories in national elections, the indy movement remains static, spectating Scottish and British governments “stuck in a perpetual fistfight with neither landing any blows”.

At least those were the words of Foley and Wray. Since the publication of Scotland After Britain, the British state has landed two significant blows on the SNP. The first was a Supreme Court ruling blocking the Scottish Parliament from legislating for a second referendum. The second, the blocking of Gender Recognition Act reform with a section 35 order, despite the majority of the devolved parliament voting in favour of it.

Foley and Wray warn that if control over the independence movement cannot be won back by the left, an independent Scotland could be dominated by business interests and unaccountable think tanks. This would be a difficult situation to reverse. Even worse, the non-confrontational approach of the SNP may fail to win independence altogether, leading to further decades of a stagnant Scotland.

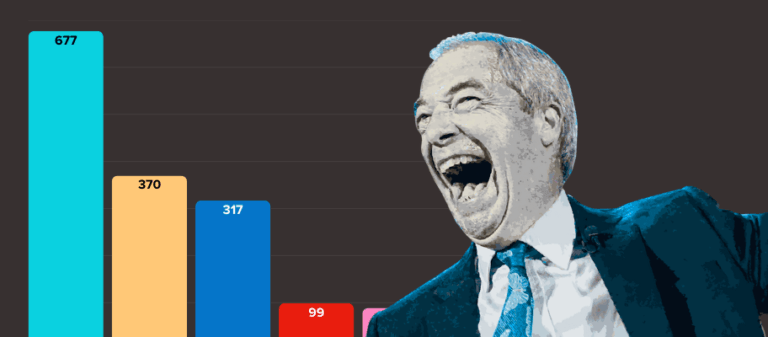

We are now moments after the fourth British general election since the independence referendum. However, instead of another status quo result, this time Labour drifted through the doors of Downing Street unopposed. The SNP took catastrophic losses (-39 seats) at the polls as Scots — many of whom had waited patiently through ten years of SNP inaction — declared “fuck it, I guess” to a New Labour 2.0.

Clearly the SNP has failed harder than Foley and Wray expected, and many now worry that the independence movement has missed its chance.

But could this failure be an opportunity for working-class radicals to take the lead now that the moderate approach has faltered?

The “Two Souls Of Independence”

Within their brief conclusion to the book, Foley and Wray adapt Hal Draper’s “Socialism From Below” theory to suggest a way forward for the left of the indy movement.

Hal Draper’s “Socialism From Below”, while perhaps overly dismissive of the gains made by 20th century socialist projects, does map onto the situation of the indy movement today. By having a movement led from the grassroots like the one which brought us close to the finish line in 2014, we can aim for a rupture from, rather than a continuation of, the global economic order. Instead of working within official channels, we can confront the state with a radical movement, resisting politicians who want to make a career out of popular anger. In short, we have a blank canvas to rebuild the march for change from the bottom up, rather than the top down.

The remainder of the conclusion gives readers a taste of the ideas and principles which socialists like those in the SSY use to support our case for a Socialist Scottish Republic. The brief summaries of radical republicanism, internationalism from below and popular sovereignty are a great jumping off point for further reading.

A wee section titled “An Agenda for Movement Renewal” is sneaked in at the very final pages of the book. The authors suggest that the independence movement should transcend political parties and that the radical-left must regroup to fight for independence. This is a strange position for Foley to hold after participating in the attempt to terminate the Radical Independence Campaign (RIC) in 2021 on the grounds that it had become too left and too radical.

By nearly dismantling RIC, Foley and associates allowed Alex Salmond to sweep up disaffected SNP supporters to The Alba Party (founded days later). Alba, though painting itself as the united front for independence, has amounted in practice to Alex Salmond’s transphobic front for independence.

Whatever point about movement renewal that James was making here certainly wasn’t informed by experience. Whether he was right or not, I’ll leave for you to decide.

Despite a few hiccups throughout it, I would certainly recommend this book to every socialist looking to brush up on their independence politics. As with all socialist texts, it is a book that demands a critical eye and is best read with a degree of scepticism about the worldview of its authors.