Oppenheimer’s writer and director, Christopher Nolan, is famous for his mind bending sci-fi thrillers. Part of his formula for success sees him play with some of society’s greatest fears. Climate collapse. The horrors of war. Weapons of mass destruction. And Nolan plays into our fears as individuals, such as losing grasp over what’s real and unreal, losing our memories, or being trapped inside a dream.

The remarkably underrated “TENET” was Nolan’s previous, and still today his most costly original project. Hidden under layers of awe inspiring video FX magic and a discombobulating plot, this story originates with a civilisation from the future attempting to reverse the flow of time away from the ravages of catastrophic climate collapse. To save the world, a scientist invents a formula, the Algorithm, that would achieve a total “inversion” of time, at the cost of erasing life in the past. The film takes place in that past (our present), following a secretive organisation attempting to prevent the use of the Algorithm. Confused yet? It might take you more than one watch and a few explainer videos to fully understand it.

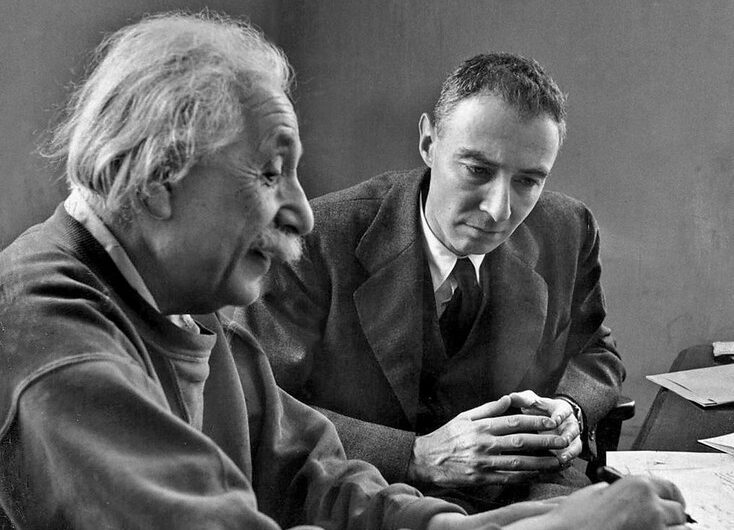

Despite having been broadly overlooked by moviegoers due to its unfortunate release between the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns, TENET is notable because it invites viewers to reflect on the role of Robert J Oppenheimer in human history. The future scientist in this story, who doesn’t actually appear on screen, is described as the Oppenheimer of her generation. After creating the Algorithm, she faces the potential risk that upon inverting time she may erase herself and her world from history.

Unlike Oppenheimer, this future scientist prevents the use of the Algorithm by scattering its pieces in physical form – at least until our antagonist, Andrei Sator (played by Kenneth Branagh), gets his hands on them. Then, just as before the atomic test in Oppenheimer, we wait with stones in our stomachs for the Algorithm to be detonated or neutralised.

Oppenheimer and the atomic bomb

Robert J Oppenheimer was one of the world’s most important theoretical physicists of his time. During World War Two he was appointed as the director of the Manhattan Project — the taskforce established to deliver the world’s first atomic bomb.

Nolan masterfully constructs the story of Oppenheimer’s life, taking inspiration from the book American Prometheus, which he had sought out after Robert Pattinson presented him with a collection of Oppenheimer’s speeches on the set of TENET.

Oppenheimer’s invention of the atomic bomb symbolised the first time in history that humanity had the ability to destroy itself. However, it turns out that this world-ending weapon could not be controlled or regulated by the scientists who created it.

The build-up to the first atomic bomb test will surely go down as one of the greatest moments in cinema history. Returning for another Nolan hit, Ludwig Göransson’s soundtrack captivates you with swelling staccatos as the test grows nearer. The use of music to convey intense feeling has been a key characteristic of Nolan’s recent works, but Oppenheimer reaches a new height.

Oppenheimer and his crew of scientists did not know for certain what would happen when they detonated the bomb. Even though their calculations suggested the bomb would be detonated safely, there was a risk that their test could ignite the Earth’s atmosphere, ending the world.

I doubt I’ll ever be hit as hard in a cinema as by the atmosphere created by the Trinity atomic bomb test.

But this film was as much about McCarthyism as it was about the invention of the atomic bomb. The story depicts a struggle between the totality of politics and the advocates of science in post-war America. Our titular Oppenheimer, skilfully played by Cillian Murphy, realises the horror of his creation only when it’s too late.

SPOILERS AHEAD: science and global politics in Oppenheimer

The 1950s saw a new era for the world, one where power was concentrated between two superpowers, who exercised incredible influence over the rest of the world. Under both powers, massive campaigns of political repression were used to curb the creeping influence of the enemy’s ideology. In America, this campaign was known as The Red Scare, or McCarthyism, named after Senator Joseph R. McCarthy who in February 1950 announced he was in possession of a list of 205 card carrying Communist Party members working in the US Department of State.

In the second half of the film, Oppenheimer enters the world of politics with naïve commitment to the greater good. He had believed that by using the bomb, a new era of peace could be ushered in, as people all over the world realised the mass destructive capability that human technology had reached.

However, his calculation is incorrect. The evaporation of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians is met with rapturous applause among the American public. The Soviet Union begins developing their own nuclear capabilities, and the race for bigger, badder bombs begins.

Oppenheimer attempts to use his positions of power — as the world’s most famous scientist and Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission’s General Advisory Committee — to put an end to the arms race and broker negotiation over international nuclear disarmament.

In the few opportunities where he achieves a platform, politicians and the powerful scoff at his calls for nuclear armistice, thundering ahead with Cold War conviction. To drive this point home, President Truman appears to call Oppenheimer a cry-baby when he expresses his guilt for unleashing atomic weaponry on the world (this actually happened!)

After small involvements with the Spanish civil war, trade union activism, and association with the Communist Party, comrade Oppie’s younger days come back to bite him. What follows is a relentless McCarthyist witch hunt. These small and commendable acts are used as evidence by the FBI of his sympathy to the Soviet Superpower. He is trialled by kangaroo court, and his role in public life is destroyed.

The film ends on a chilling note, as Oppenheimer reflects on what he has created, and we, the viewers, are also left to reflect on the nature of scientific development in a world system controlled by ambitious and unaccountable elites.

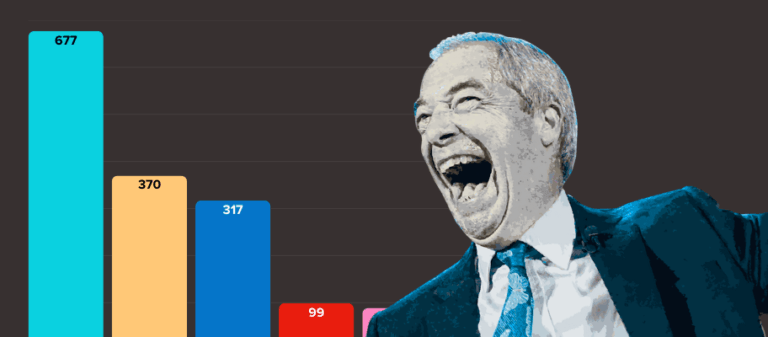

We now live in a world with over 9,576 Algorithms ready and waiting to begin the chain reaction ending in apocalypse. All it may take is one trigger-happy world leader to unleash it all.

In our system of global capitalism and international conflict, every great scientific advancement we make, no matter its potential to save lives, will be weaponised by the powerful.

So long as capitalism rules the world, scientists like Oppenheimer are doomed to the same fate as sorcerers — who are no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom they have called up by their spells.